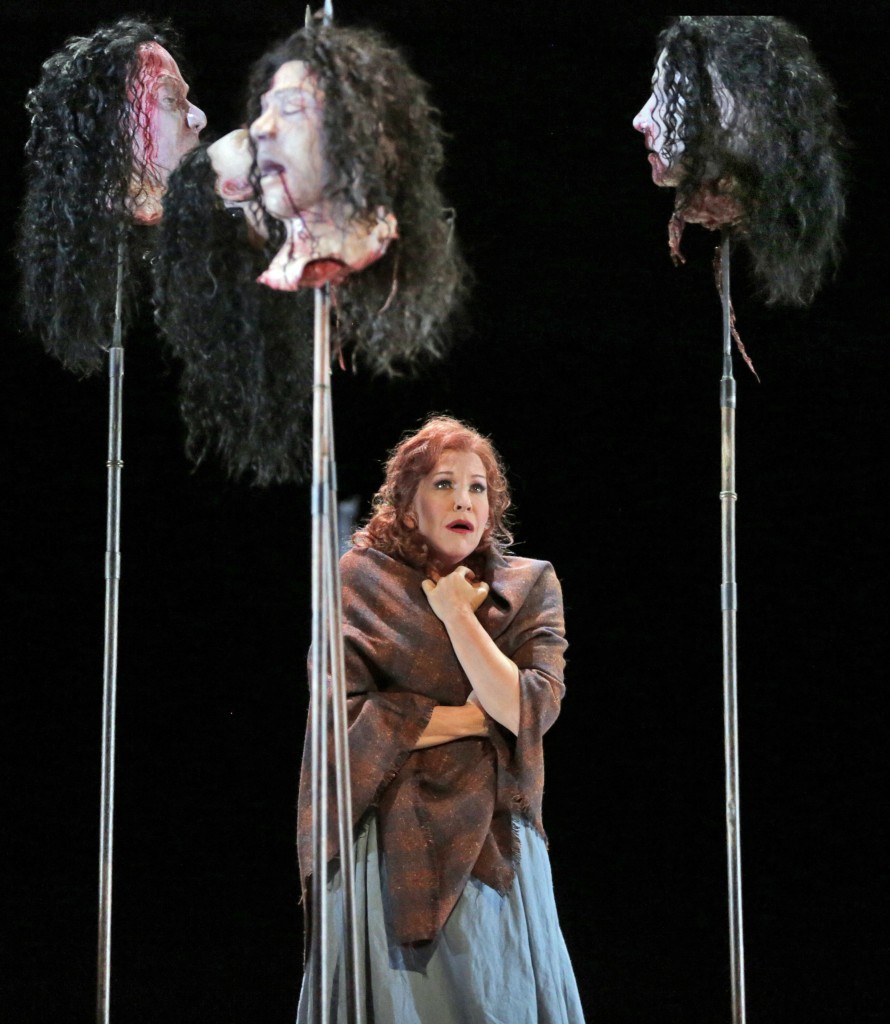

Vocal splendor in Santa Fe: Rossini’s ‘La Donna del lago’

La Donna del lago

The Lady of the Lake

Composer Gioachino Rossini

Libretto by Andrea Leone

Performed in Italian

Santa Fe Opera, August 14

Review by David Gregson

Way back in 1968, RCA Victor, a major classical record label at that time, released what we so quaintly term in our more technologically advanced world of today as a “12-inch black vinyl disc” entitled Rossini Rarities. Yes, LPs are now making a pop-music comeback, but that’s another story. The recording featured artist soprano Monserrat Caballé, an international phenomenon at the time and now a beloved legendary diva. The selections offered were arias from La donna del lago, Otello, Armida, Tancredi, and L’Assedio di Corinto. I adored the album, but it has taken me virtually an entire lifetime to see all of these operas performed fully and live on stage. Now, with Santa Fe Opera’s memorably wonderful production of La donna del lago, my 1968 rarities list is complete.

Composed to a mildly confusing and cliché-ridden libretto by Andrea Leone Tottola, La donna del lago is a giddy hash flavored with all the standard operatic emotions of love and jealousy, bitter rivalries and warlike aggression. The story originates in a narrative poem by Sir Walter Scott, albeit via a French translation. It was the first Italian “Scottish” opera, the most famous that survives today being Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor. A prominent feature of Rossini’s piece is the familiar “lover in disguise,” and in this case the lover is none other than King James V of Scotland prowling about with the unlikely nom de guerre, Uberto — a dead giveaway, I should think, that something sneaky is afoot.

La Donna, or the lady of the drama, is Elena, whose aquatic appellation derives from the simple fact that she rows back and forth over Loch Katrine on a regular basis. The opera’s title suggests something considerably more magical! Fortunately or unfortunately, Elena’s father is Duglas d’Angus, one of King James’ former tutors; but Duglas and his Highland Clan commanded by Rodrigo di Dhu are in rebellion against the monarch. Meanwhile, Elena is madly in love with Malcolm Goerne whose alliance with James wavers when he learns that Elena’s father expects her to marry Rodrigo! What is “Oy vey!” in Scottish? And as if Elena doesn’t have enough romantic problems on her hands, Uberto starts chasing her about. By the time Act Two rolls around, Uberto, who claims a very close connection to the King (for he is, in fact, the King), gives Elena a ring as a sort of pledge to protect her during the Scottish civil war.

Before this mess is straightened out, Rodrigo is killed in battle (eliminating unwanted lover number one), and Uberto reveals himself as James and honors his pledge (eliminating lover number two — in a remarkably generous and clement gesture), and Elena is free to marry Malcolm. And so the opera ends happily with Duglas (the impressive bass Wayne Tigges) pardoned and Elena expressing her unbounded joy in the fabulously florid rondo, “Tanti affetti,” one of the great showpieces in opera.

Let me say, if nothing else at all were going on in Santa Fe this summer — and there’s plenty, including a major chamber music festival — it would have been worth the trip from Hobart, Tasmania, to hear American mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato sing “Tanti affetti” — just that bit alone! Is there a voice today to equal hers in richness and supple beauty? Is there an artist who so thoroughly inhabits a role, even when it is the frailest sort of bel canto confection? Is there anyone with such an accomplished technique when it comes to the music of Rossini? Perhaps. But when you hear DiDonato, it is damned hard to imagine who that mezzo-soprano might be.

But even as I lose myself in bubbling enthusiasm, I need to say, DiDonato was well matched here in Santa Fe with some highly worthy colleagues. First, there was another mezzo of a somewhat deeper hue, Sicilian mezzo-soprano Marianna Pizzolato. She was assigned the trouser role of the warrior/lover, Malcolm, who does in fact get the girl at the end of the opera. Pizzolato’s warm color remains consistent throughout her registers, only changing slightly in timbre as she reaches for some remarkable high notes now and then. She does not cut a very romantic figure on stage, but this is of little or no importance when the singing is so accomplished. This woman is everything that Cecilia Bartoli with her aspirated machine-gun singing is not.

La donna del lago belongs to that special category of opera in which there is more than one leading tenor role: Uberto (James) and Rodrigo are astonishingly difficult coloratura roles, and the characters get to show off in spectacular solos and ensembles. One of Rossini’s most endearing features is setting everybody going at once and even throwing in a full chorus for good measure. The two amazing tenors here in Santa Fe are American Lawrence Brownlee as Uberto and American René Barbera as Rodrigo — and it’s fascinating to compare the two. Brownlee has the warmer timbre, and his agility is already widely celebrated at the Met and elsewhere; Barbara’s sound is brighter, more ringing than Brownlee’s. Together they helped make for an evening of dazzling vocalism.

This production, well stage directed and largely without any gimmicks by Paul Curran, was so designed by Kevin Knight so as to allow the audience a view of the desert landscape all evening. Most of the set is a textured floor with moveable sections and a peasant hut that pops up when needed. As the sun actually set behind the distant Jemez Mountains, Elena was singing of the onset of evening. Curran’s one odd touch was a sort of shirtless Blue Man troupe that came on and writhed about — but they were apparently supposed to be seers seeing. It looked a bit to me like an out-of-place modern dance exercise. Knight’s costumes were mostly dusky, I thought, but they did evoke Scotland and a sense of period. The Scottish flag with the Cross of Saint Andrew was greatly in evidence during the wonderful warlike male choral scenes (director Susanne Sheston). And when the men slathered their bared chests with blue paint crosses, Mel Gibson’s Braveheart flashed momentarily through my mind.

The excellent orchestra was conducted with brisk efficiency and conservable élan by Stephen Ward.

Elena – Joyce DiDonato

Malcolm Groeme – Marianna Pizzolato

Uberto – Lawrence Brownlee

Rodrigo di Dhu – René Barbera

Douglas d’Angus – Wayne Tigges

Albina – Lacy Sauter

Serano – Joshua Davis

Betram – David Blalock

Conductor – Stephen Lord

Director – Paul Curran

Scenic Designer – Kevin Knight

Costume Designer – Kevin Knight

Lighting Designer – Duane Schuler

Choral Director — Susanne Sheston

Thanks, David, for giving your readers such a vivid picture of bel canto luxury in Santa Fe. 15 or 20 years ago, who would have thought that opera stages in the U.S. would be populated by such accomplished bel canto powerhouses? And so many young Americans among them?