Superb Mozart “The Magic Flute” in Santa Fe — 2006 Season

Review by Gerald Dugan: August 6, 2006, Santa Fe, New Mexico

Mozart’s last opera, The Magic Flute (Die Zauberflöte), like so many other late works of genius, is a kind of last will and testament, bequeathing to humanity, not a realistic portrait of life as it is, with all its petty jealousies, deceptions, cruelties, and acts of revenge, but instead a vision of an ideal realm of life as it could or should be, in which our sins against each other are mutually forgiven, and a spirit of compassion for the frailties of human beings inaugurates a “brave new world,” a Golden Age, in which all men and women are treated justly.

This utopia is not merely an Enlightenment ideal. It exists as early as the ancient Greek Oresteia of Aeschylus, in which Orestes is forgiven the murder of a mother who killed his father, and his tormenting Furies are turned into Kindly Ones, who will henceforth guard Athens against its enemies. Such as vision of a just world dominates the last tragedy Sophocles wrote, Oedipus at Colonus. The romance marking Shakespeare’s official farewell to the stage, The Tempest, is imbued with much the same spirit, as are Beethoven’s setting of the Schiller “Ode to Joy” in his Ninth Symphony, and Wagner’s treatment of the Montsalvat community of worshippers, after the threat of Klingsor’s curse has been lifted, in Parsifal. This forgiving of all human foolishness animates the deeply humane final scene of Verdi’s Falstaff as well. And not even the avalanche that kills Rubek and Irene at the conclusion of Ibsen’s last play in his realistic cycle, When We Dead Awaken, can crush their shared hope of humanity eventually attaining a “peak of promise,” a true liberation of spirit commensurate with our highest hopes and dreams.

It should not surprise us (although it irritates radical feminists, with their insulting prattle about Dead White Male Culture — i.e., the only kind of culture we possess ), that these gods of art throughout thousands of years of Western Civilization invariably depict God-like figures as their alter-egos in their final works, masters of their separate ideal realms. Almost all these fictional deities are bass-baritones, who speak the poetry and sing the songs of the mature masculine authority figure, the lord of all he surveys: Oedipus at Colonus, Prospero, Sarastro, Gurnemanz, the Falstaff of Verdi’s final fugue, and Ibsen’s aged philosophical sculptor, Rubek. (The figure who interrupts the orchestra in the last movement of Beethoven’s Ninth is neither the tenor nor the soprano nor the mezzo-soprano, but the bass-baritone, who alone possesses the God-like authority to demand that the orchestra change course, and accompany the singers and the chorus in the musical setting of Schiller’s poem.)

For years I have wondered if Mozart had ever read or seen a performance of Shakespeare’s The Tempest, since the Bard’s last romance is so similar in plot construction, characterization, and atmosphere to Mozart’s last opera, The Magic Flute. I am indebted to John Kotowski, long-time lecturer at the Ghost Ranch of Santa Fe’s Opera III seminar, for having researched this question, and discovered the answer. Yes, Mozart had read a German translation of The Tempest, proposed to him in the last year of his life as a possible subject for a commercially popular “Zauber” opera (or magic opera) by a potential librettist. While he enjoyed the subject, he was too busy (with the Requiem, La Clemenza di Tito, and The Magic Flute) to work on such a project.

Nevertheless, there are these similarities to The Tempest (also being presented in Santa Fe this year in the American première of the Thomas Adès opera). Both central figures have something supernatural about them: Prospero as a magician of genius, Sarastro as the head of a Masonic religion; both have daughters (whether actual or unofficially adopted) whom they wish to see married; both choose to test young princes as possible fiancés for this young woman, even though each prince has been allied, either by birth or by an earlier, mistaken choice, to a sworn enemy of the father figure; and, finally, each of the older authority figures has acquired helpers and servers to gain what he wishes: Caliban and Ariel for Prospero, Papageno and the three angelic boy sopranos for Sarastro, the former earthy and impatient, the latter, other-worldly and serene. When the father-figures are successful in seeing a new generation launched with a marriage ceremony, they forgive their old enemies (at least they do in this Magic Flute, in which the Queen of the Night — but not, alas, her servants — the Three ladies) and join the wedding party).

So, other than that, how did you enjoy the play Mrs. Lincoln?

This was one of the best directed, designed, conducted, acted and sung Magic Flutes in my experience – a redemption of sorts for Santa Fe after its last Flute, a famously bad Jonathan Miller production that took place in a contemporary Swiss resort hotel, with snakes chasing Tamino in the lobby, and animals disturbing the paying guests whenever Tamino played his flute. (So difficult to find properly trained bellhops these days!)

Under the capable direction of the Englishman, Tim Albery (who also provided the translation of the spoken dialogue; whatever was sung was performed in the original German), this Magic Flute eschewed Egyptian-Masonic décor and costumes in favor of an unchanging abstract set — one large wall to our right painted with thousands upon thousands of squares or gold leaf, and one facing wall to our left, painted with thousands upon thousands of squares of silver leaf. Each of these walls featured convenient openings for rapid scene changes – which avoided the lengthy stage waits of more painterly productions (i.e., those designed by Chagall and Tsypin at the Met; Hockney in San Francisco and New York); Scarfe in Los Angeles; and Sendak in San Diego).

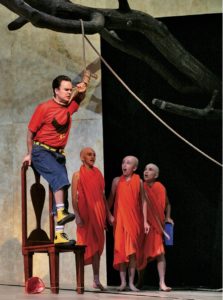

Like the set, the costumes were the work of the inventive German designer Tobias Hoheisal, whose concept was to design clothes from different eras and parts of the world, to emphasize the universal aspects of Mozart’s final masterpiece. Sarastro and his Masonic Brotherhood wore 17th or 18th century puritanical black coats, knickers and knee socks, like Amsterdam businessmen in one of Rembrandt’s group portraits. Their white wigs also reminded me of the American constitutional committee in Philadelphia in the last quarter of the 18th century. The Queen of the Night and her three ladies wore sumptuous Elizabethan garb (the Queen’s gown studded with gazillions of rhinestones to suggest the starry firmament.) The Tamino-Pamina pair wore more or less contemporary outfits: elegant slacks, T-shirt and white shirt for Tamino, a lovely, simple white gown for Pamina. Monostatos and his thuggish crew wore gray Nazi uniforms – which became an hilarious sight-gag out of The Producers when the magic, harmony-producing glockenspiel was played, and these brutal militarists, began dancing a gemütlich minuet with each other. The charming, youthful choir of three spirits (Sean Lunberg, Kallyn Duran, Breanna Hastings) sang with a purity that well suited their bald heads and saffron robes – they were like three youthful finalists to become the next Dalai Lama. Finally, there was Papageno, his Papagena, and their numerous children and grandchildren – all dressed in bright red tops and trousers, like a troupe of California surfer dudes, their chicks and their rug rats, paragons of the cheerful vulgarity of American egalitarianism, on their way out the door to Wal-Mart.

Various people who have no appreciation of elegant minimalism (or any other “ism” that is not at least 200 years old, for that matter) complained of this Flute’s “ugly” set, and the oddity of mixing periods and styles of costumes. I thought the set, wonderfully lit by Jennifer Tipton, was as beautiful as the first Flute I ever saw, the legendary one in Salzburg in 1967, created by Brecht’s great designer, Teo Otto. And I thought the costume choices were also witty and apt, especially when it came to hearing the spoken dialogue in English – when that language was given a French accent by the Pamina, a British accent by the Tamino, and Italian one by the Sarastro, and a slangy American one by the Papageno – a universally representative cast, in other words.

British conductor William Lacey’s handling of this great score was impeccably right, in that it was neither raced through (as in so many “original instrument” Flutes); nor was it too reverently slow, in the Klemperer manner of genuflecting before one of the great monuments of Western Civilization. It alternated between breeziness and profundity with ease. My only objection was not being able to applaud the overture, whose majestic ending transitioned too quickly into the outrageously funny opening image director Albery had devised, of the hapless Tamino trapped inside the mouth of a giant snake, about to meet Jonah’s fate inside the whale. This was, however, the cleverest beginning of any production I’ve seen.

The cast was up to the highest Santa Fe Opera festival standard. Natalie Dessay was a wondrous Pamina, reaching heights of tenderness in her second act “Ach, ich fühls” aria addressed to a Tamino who has been forbidden to answer her, as part of the trial Sarastro is putting him through. I far preferred her Pamina to her role in that crowded, claustrophobic Sonnambula she was stranded in a few years ago. The English Toby Spence was a dashing, full-voiced Tamino, ideally suited to this role. After a somewhat unfocussed first act, Andrea Silvestrelli came into his own as a truly magnificent Sarastro, with a wonderfully easy, dark bass voice that reminded me of Gottlob Frick’s when it wasn’t reminding me of today’s reigning Gurnemanz, Kurt Moll. Joshua Hopkins’ Papageno was delightfully funny and consistently well sung, as was the Papagena Anaya Metanovic. I must confess, I am a total sucker for the stuttered Papageno-Papagena recognition scene. When everyone else is merrily laughing, I find myself weeping uncontrollably, it’s so damned unbearably beautiful. Moments like that one are the reason the word “sublime” was invented. (I also sometimes wonder if Samuel Beckett stole the comic failed suicide bit in Waiting for Godot from Papageno’s failed attempt, one that also involves a hangman’s knotted rope and a tree.)

While the Queen of the Night’s three ladies (Sarah Gartshore, Paula Murrihy, and Lucia Cervoni) made up an excellent ensemble, and David Cangelosi proved an excellent Monostatos, both villainous and funny, Heahter Buck’s Queen of the Night was more impressively acted than it was sung. She has the right command for this role, but her staccato high notes in the second act aria could only be sustained at a much slower tempo than conductor Lacey seemed comfortable with.

Review by Gerald Dugan.

Cast

Pamina — Natalie Dessay / Susanna Phillips (Aug. 22 and 25)

The Queen of the Night — Heather Buck

Tamino — Toby Spence

Monostatos — David Cangelosi

Papageno — Joshua Hopkins

Sarastro — Andrea Silvestrelli

Conductor — William Lacey

Director — Tim Albery

Scenic & Costume Designer — Tobias Hoheisel

Lighting Designer — Jennifer Tipton