Archive for August 2012

Santa Fe Opera presents a welcome rarity: Szymanowski’s “King Roger”

LAURA WILDE (DEACONESS), MARIUSZ KWIECIEN (KING ROGER), ERIN MORLEY (ROXANA), DENNIS PETERSEN (EDRISI) & RAYMOND ACETO (ARCHBISHOP). Photo by Ken Howard.

Santa Fe Opera: Karol Szymanowski’s “King Roger.”

Now playing in summer festival repertory.

Review of the August 9 performance by David Gregson.

Ancient Greek tragedy grew out of an annual religious celebration devoted to the demigod, Dionysus, whose father was the Olympian Zeus and whose mother was the mere mortal, Semele. Handel wrote a perfectly marvelous English language oratorio about this woman, a work that was memorably performed as an opera here in Santa Fe in 1997; but this year’s most unusual item, one closely related to the Dionysus myth, is Polish composer Karol Szymanowski’s “King Roger,” a virtually autobiographical opera that portrays the inner turmoil of a man torn between two opposing forces of his nature. The libretto was written by the composer himself in collaboration with his cousin, Jaroslaw Iwaszkiewicz, a notably gay Polish poet who married and had two daughters, but who is alleged to have been Szymanowski’s lover. For that reason — and here one commits the famous literary critic’s no-no of the “biographical fallacy” — many critics regard King Roger as a repressed homosexual looking for a way out of the closet.

But, is that what this sumptuously scored opera is all about? Perhaps — but as presented in a handsome production designed by Thomas Lynch and directed by Stephen Wadsworth, this story, set in 12th-century Sicily, is thoroughly ambiguous. Multiple interpretations are possible. To begin with, the inner life of the titular king is largely revealed through lyrics expressive of indecision, doubt and confusion, and the external behaviors of the other characters are mysterious in their easy changeability. King Roger, sung here by the celebrated Polish baritone Mariusz Kwiecien, spends almost 90 minutes going through agonized contortions suggesting everything from severe stomach cramps to the recovery spasms caused by drug addiction. An elaborate physical pantomime seems to be required for us to know just what is going on inside Roger’s brain. This is not to denigrate Kwiecien’s singing, which is superb, or even his acting: the opera seems to demand this sort of performance. In any event, repressed homosexuality is not anything clearly conveyed as the story begins.

The basic plot line is simple. In Act One, the “Byzantine Act,” a mass is taking place in a Byzantine cathedral in Palermo (an inspiration for some gorgeous choral writing by Szymanowski), when we learn that a troublesome Shepherd (the wonderful, golden toned lyric tenor William Burden) is wandering around preaching about the glories of a pagan deity. This deity would be the Shepherd himself, of course, since this Shepherd, just as in the great “Bacchae” of Euripides, is really Dionysus. In the Euripides, Dionysus is distinctly not a law-and-order man. He is out for revenge on Pentheus (changed to King Roger by Szymanowski) who is suppressing Dionysus’s brand of free-thinking, free-spirited wine-and-song revelry in the city of Thebes. In “King Roger,” the Shepherd’s motives are not clear at first. The people, led by the Archbishop (an authoritative Raymond Aceto) would like to see him executed; but Roger’s wife, Roxana (lovely sounding soprano Erin Morley), is drawn to the Shepherd because, as some people have so crudely suggested, she “isn’t getting any at home,” and soon everyone else is jumping on the free love bandwagon.

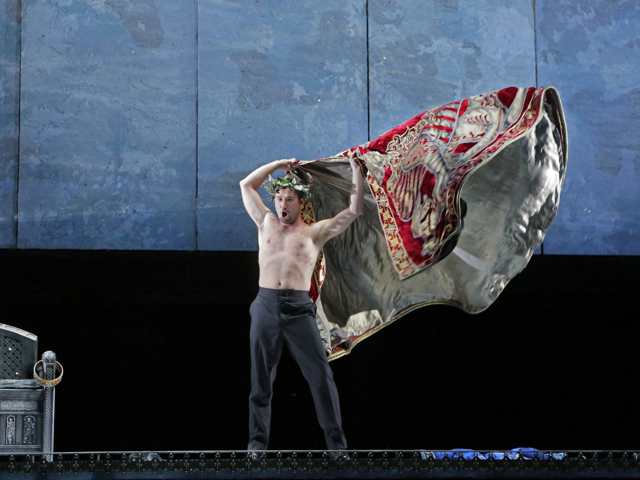

An Arab scholar named Edrisi (the excellent Dennis Petersen) is Roger’s close friend and confidant. Together the two men hope to interrogate and ultimately execute the Shepherd, but the Dionysian charisma is impossible to resist. The Shepherd is the Mr. Hyde, so to speak, to Roger’s Dr. Jekyll. In the “Bacchae,” Dionysus actually convinces Pentheus to dress up as a woman — in order to recognize his female side and to be able to spy on the demigod’s worshippers, the female Bacchants or Maenads as they are also called. (Bacchus is one of many names for Dionysus.) Nothing so fantastic happens to Roger, but he does gradually succumb to the Shepherd’s more sensual blandishments. I should add that Mr. Burden, who used to display (and may still be capable of doing so for all I know), a rather buffed torso, did not do so on this occasion. A glimpse of skin might have made him more convincing as as sexual lure. He looked more the Shepherd than a demigod. As it turned out, only Kwiecien bared any flesh.

Now we leave Act Two, the so-called “Oriental Act.” By Act Three, the very significantly named “Greco-Roman Act,” Roger appears more conflicted than ever. He has seemingly abandoned his responsibilities as a leader, his subjects are cavorting about the hillsides, and when he calls out for his wife Roxanna, he gets the Shepherd instead. A close friend assures me the Shepherd and Roger more than once “violated personal space” by coming within kissing distance of one another — and while this is so, no kissing took place that I could see. After some more odd behavior, Roger lights a fire in honor of Dionysus, and (in this production) strips off his shirt and whirls his robe about like a dancer from the Moiseyev Dance Company on tour. But, curiously, the opera quickly concludes with Roger choosing solitude over a life “in the land of rapture.” Roger unambiguously salutes the morning sun. If he had been Pentheus, poor soul, he would have been literally torn to pieces by the Maenads, one of whom is his own mother, Agave.

Both “The Bacchae” and “King Roger” are moral puzzles, and I imagine all people who leave this opera experience some degree of mystification. The music they find has been wonderful: a huge, thickly scored orchestra that evokes everyone you can think of from Palestrina to Scriabin, Mahler, Wagner and Debussy; richly textured choral music (bravo chorus master Susanne Sheston!); complex harmonies, polytonality, and Renaissance polyphony. And all of it superbly coordinated by conductor Evan Rogister and fabulously played by a super-sized Santa Fe Opera Orchestra.

But if the Greek sun god Apollo stands for law and order, for rationality, for solitude, and for clear, no-nonsense masculine thinking; and if he also stands in opposition to irrational Dionysian social gregariousness, sexuality and an abundance of wine — well, the moral of the story seems to side with staying in the closet. In the end, it is not a theme of gay liberation — or any kind of liberation with regard to responsibility to society as a whole. Perhaps Roger has attained a sort of Jungian individuation? Or has he dropped out altogether? If he has achieved an inner piece, I am not certain what it is. That he is liberated is clear, but from what? The solitude of a hermit drives one to madness (just to drag Sigmund Freud into this mix!)

A final word about the so-called Apollonian and Dionysian forces in art: German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche’s “The Birth of Tragedy” is familiar to all serious students of drama — or at least it should be — and dedicated Wagnerians should probably know something about it as well. In this famous book about Greek tragedy, Nietzsche traces tragedy’s contrasting and often conflicting forces through drama while making the claim that Apollo possesses the text (the poetry, really), while Dionysus is present in the choral singing and dancing.

What is easiest for anyone to understand, however, is that the human personality is reality a duality: good and evil, sacred and profane, id and ego, the conscious and the unconscious, the self and the shadow, and the Apollonian and the Dionysian.

Roxana – Erin Morley

Shepherd – William Burden

Edrisi – Dennis Petersen

King Roger – Mariusz Kwiecien

Archbishop – Raymond Aceto

Conductor – Evan Rogister

Director – Stephen Wadsworth

Scenic Designer – Thomas Lynch

Costume Designer – Ann Hould-Ward

Lighting Designer – Duane Schuler

Choreographer – Peggy Hickey

Chorus Master — Susanne Sheston

For complete schedule and ticket information, please visit Santa Fe Opera.