Archive for August 2006

Santa Fe Opera Presents Thomas Adès “The Tempest”

Review by Gerald Dugan, August 18, 2006

[Please note: The political opinions expressed in this review do not necessarily reflect those of the Opera West site administrator.]

After experiencing Santa Fe Opera’s thrilling American première production of the equally superb opera by Thomas Adès inspired by (but not necessarily literally based upon) Shakespeare’s farewell to the stage, The Tempest, I was anxious to re-read the Bard’s text in my old, dog-eared edition of the play I have owned since my college days. When I came to Prospero’s memorable lines following the magic masque he produces to celebrate the forthcoming nuptials of his daughter, Miranda, and his future son-in-law, Ferdinand, I was struck by the fact that the masque symbolized not merely the three-dozen imaginative worlds Shakespeare had created for the stage. More importantly, the masque also symbolized the fate of our own, increasingly fragile earth, ruled as it has been for thousands of years by the voracious and aggressively self-destructive human animals. And I imagined the arrival, 500 or so years from now, of visitors to our small planet (as Gore Vidal calls it) from another galaxy, who discover nothing here but a desert inhabited by ubiquitous annoying cockroaches. A week or so into their expedition, they find these words etched into a block of marble in the sands:

Our revels now are ended. These our actors,

As I foretold you, were all spirits and

Are melted into air, into thin air:

And, like the baseless fabric of this vision,

The cloud-capp’d towers, the gorgeous palaces,

The solemn temples, the great globe itself,

Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve

And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,

Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep.

The expedition guesses this must have been written shortly before the catastrophic extinction of the human race. However, when an ancient library is excavated a few months later ascertains that these are the words of the finest poet and dramatist who ever wrote in English, she also finds that they were written half a millennium before the extinction of human life, making Shakespeare as prescient as Nostradamus. And, the vanishing “cloud-capped” towers seem eerily resonant of 9/11. [Please see footnote.]

The masque may well be the most famous scenes in Shakespeare’s play, and Prospero’s speech one of the most famous in all of English literature. But neither the masque nor speech are dramatized in Adès’s opera with its libretto by Meredith Oaks. These collaborators decided, in all probability, that you cannot add music to what is already incomparable “word music,” as Bernard Shaw called the dramatic poetry of his chief rival. Besides, in this radically stripped down, classical version of the story, the masque has no dramatic function in terms of the central action of the piece: Prospero’s creating a storm at sea to trap his old enemies on his enchanted island, where he can nettle them for their crimes against him, and eventually confront them with the fact that they had conspired against him 12 years ago to usurp his position as Duke of Milan. By allowing his daughter, Miranda, to become engaged to Prince Ferdinand of Naples – extremely reluctantly, in this version – he succeeds in retrieving his dukedom from his usurping younger brother, the opportunistic Antonio. Forgiving his former enemies, he gives up his magic powers by breaking his staff, drowning his book, and freeing his supernatural helpers, the earthy Caliban, and the ethereal, otherworldly Ariel. He returns with the others by the ship he has magically restored to them, heading for the Italy he had been forced to flee, ending his exile.

From another point of view, suppose Shakespeare’s speech does prophesy the end of the world? What then? Shall we hope this disaster occurs later rather than sooner – later, for instance, than two months from now, when the November elections occur? Does anyone actually think that our smirking Commander-in-Chief will go to the Senate to ask permission for a war with Iran? Isn’t far more likely that he will secretly give our ally, Israel, the go-ahead to nuke Tehran and the underground Iranian nuclear facilities? If that happens, does Pakistan become our former ally, once it has nuked Tel Aviv and Jerusalem? And will Israel then unleash its considerable nuclear firepower on each and every Arab capital in the Middle East, Africa, and Indonesia? And will our American elections be cancelled, due to nuclear winter? Covent Garden has just announced that it intends to revive Adès’ The Tempest next year. Will there be a London or a “next year” by that time? What’s the point in my declaring that this opera is probably the finest new opera I have ever seen, perhaps the greatest since Berg’s Wozzeck or Puccini’s Turandot, or that Adès is probably something more significant than the next Britten, just as the Wagner of The Flying Dutchman was much more significant than the next Carl Maria von Weber? What if I were to declare that he may well be the Verdi or Wagner of the 21st century, the answer to all our hopes for a rejuvenated, genuinely vital opera scene? What will that matter if there is not a 21st century?

But let us pretend for a moment that we have world enough and time to discuss why The Tempest is such an extraordinary opera?

One: Adès, both in this opera and his earlier Powder Her Face (which I saw in its American professional première staging at Long Beach Opera) has his own unique voice as a composer; he writes music that is authentically his own, that reminds one of nobody else. He is a genuine original.

Two: In The Tempest, Adès and his librettists have done something quite daring to their central protagonist, Prospero. The calm, philosophical magician of Shakespeare’s play, who exhibits few if any overt expressions of rage at his fate, becomes much more of a human being in this opera in that he gives in to his emotions of rage, bitterness, and sadistic joy at causing his enemies discomfort. If he is god-like in Act One, he resembles the angry Wotan of Die Walküre’s Act Three. Instead of fostering the relationship between his daughter and young Prince Ferdinand by testing the prince with various tasks, he paralyzes the prince and buries him up to the waist in the sand, because he had refused to trust his daughter with the son of his bitter enemy, Alonso, the King of Naples. This irrational, angry act makes his emotional journey to becoming more merciful and forgiving by the end of the opera that much more moving. (The progression is similar to that of Zeus, the unseen god of gods in the Oresteia of Aeschylus: the god of animalistic revenge in the Agamemnon becomes, through his agents Apollo and Athena at Orestes’ trial for matricide, the evolving deity who tempers justice with mercy, turning the Furies into Kindly Ones, who will guard Athena.)

Three: Finally, Adès is equally innovative musically in his treatment of Prospero’s two supernatural helpers, Ariel and Caliban. After witnessing Adès earlier opera about the notoriously promiscuous Scottish Duchess of Argyll of the 1960s, I didn’t think this composer could get any more daring in his use of coloratura than the comic heights of that opera, in which the Duchess greets a hotel bellboy by walking upstage center to him, kneeling in front of him, unzipping his fly, and performing a Lewinsky on him, at the same time warbling a coloratura vocalise. But what Adès has done with Ariel’s stratospheric, unearthly coloratura might well be termed “coloratura squared,” because it is unlike any coloratura anyone has ever heard before. (I half expected every dog on Santa Fe mesa to begin howling every time the incredible Cyndia Sieden let those tiny, bell-like notes fly.) I will never forget her lie to Ferdinand about the supposed death of his father, the king of Naples, every quiet word of which was clearly audible to a totally spellbound audience:

Full fathom five thy Father lies,

Of his bones are Corral made:

Those are pearls that were his eyes,

Nothing of him that doth fade,

But doth suffer a Sea-change

Into something rich & strange

Sea-Nymphs hourly ring his knell.

Hark now I hear them, ding-dong, bell.

Adès chose to emphasize the naiveté and lonely sweetness of Caliban, instead of his more savage and threatening side, by casting him as a lyric tenor, instead of the bass-baritone usual in most stage productions. His haunting second act aria about his ownership of the island before the ungrateful Prospero stole it from him was movingly sung by the excellent William Ferguson who was nothing less than heartbreaking when everyone left the island at the end, and he could not figure out if they had ever existed, or it they were merely figments of that dream he’s awakened from earlier, “and cried to dream again.” (I wonder if this invention of Mr. Adès and Ms. Oakes – Caliban alone on the island at the end – is derived from Vladimir’s final speech, so full of existential loneliness, in Beckett’s Waiting for Godot : “Was I sleeping while the other suffered? Am I sleeping now?”) In any event, it is a nice touch to bring the opera to close with a haunting pianissimo duet between the newly freed Ariel and Caliban.

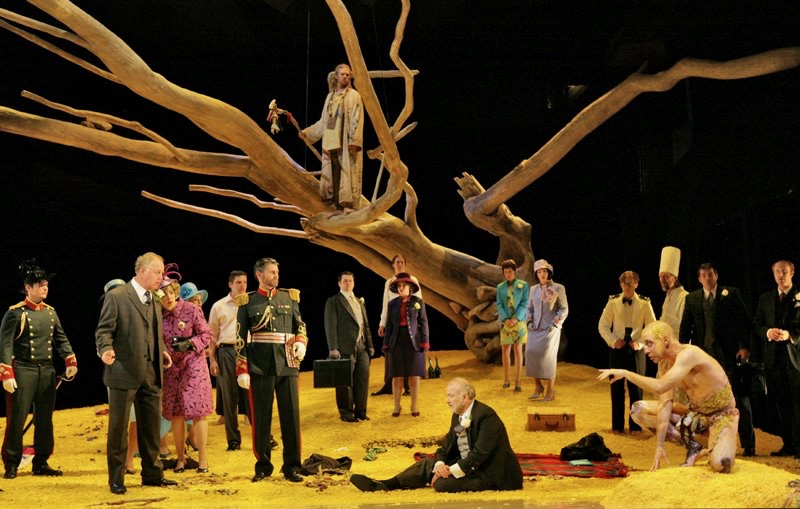

As for the Santa Fe production, I have only a few minor cavils with Jonathan Kent’s decision to costume all the visitors to the island in modern dress. Yes, we get the contemporary political implications in its exposé of criminality and deceit behind officialdom’s closed doors; but people in modern suits pulling swords rather than guns on each other looks too anachronistic, even for the most casual of casual Fridays. That being said, Paul Brown’s gowns and suits are elegantly designed and beautifully constructed, and his set – a huge barren oak sprouting from the bright yellow sands of a desert island (which can magically turn into quicksand for the unwary, swallowing them up and disgorging them by turns) – is nothing less than a marvel. And Kent’s staging of even the most complex crowd scenes is masterfully precise.

Alan Gilbert’s conducting, and the orchestra’s playing of this intricately knotty, uniquely modern and yet lyrically lonely score, was absolutely transcendent. Gilbert will be sorely missed in Santa Fe next season, during his European sabbatical.

The cast, as usual, was extraordinarily solid in just about every case. It was headed by the gifted Rod Gilfry as a majestic, powerful, yet utterly human Prospero. Others were fine as well. The young couple, Miranda and Ferdinand (Patricia Risley and Toby Spence), possessed attractive voices and evoked considerable empathy for their characters. The veteran Rossini tenor Chris Merritt was superb as the grief-stricken Alonso, convinced that his son, Ferdinand, has been lost at sea. He effectively conveyed this kingly figure’s guilty conscience over his betrayal of Prospero as well, goaded by Antonio into nearly killing Alonso before Ariel prevents it. Gwynne Howell was in excellent form as Gonzalo, who had earlier aided Prospero in escaping Italy. Howell’s plangent bass anchored many of the group scenes with its overtone of compassion for others. As Prospero’s supposedly ruthless younger brother, Antonio, Derek Taylor was fine throughout the evening, but truly excelled in an aria in which he refused to be forgiven by Prospero, confessing that he had always been jealous of his superior older brother. This refusal of the feat was quite Shakespearean, reminding us that Malvolio and Jacques would not reconcile themselves to others at the end of Twelfth Night and As You Like It. And Wilbur Pauley and David Hansen (Stefano and Trinculo) effectively performed their ineffectual revolt against Prospero.

This has been an extraordinary 50th Anniversary season in Santa Fe. (Reviews of all the operas appear here at Opera West.) I suspect, however, that history (if there is one) will only record this season as the one during which a magnificent new opera reached these shores from Great Britain – an opera which more than justifies Santa Fe Opera’s courageous policy of producing new operas and important American premières – this particular American première being perhaps the most important in the company’s 50-year history.

[Footnote: Memo to the Democratic nominee for President in the rigged 2000 election: You might mention this fictitious anecdote, and even quote much of Prospero’s speech, in one of your slide shows accompanying your movie, An Inconvenient Truth. The few Americans who know that Shakespeare has been dead for nearly 400 years and thus will not be running for public office anytime soon, may be more willing to believe his prophecy than that of a mere politico – especially that bit about the vanishing “cloud-capped towers,” with its 9/11 resonance. Avoid quoting the final sentence, however, about how we’re the stuff of dreams, our lives “rounded with a sleep.” That’s the closest thing that atheists and agnostics have to prayer, so it will not go down well with our gullible God-fearing.

Memo to all Republicants: On the theory that what is sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander, I am returning the favor of your removing the “ic” in my party’s name – an old trick by one of your great heroes, that infamous, lying witch-hunter and drunk, Senator Joseph McCarthy – by the simple addition of a single letter to your party’s name, in the hope that it reminds you of those enemies of the human race in Blade Runner, the Replicants. I also hope it reminds you that your own party cannot save our planet, since the criminal thugs in your White House are too busy planning World War III with Iran – an event that will bring the human race to extinction. Your party also cannot extricate us from the Iraqi quagmire, which was never anything but a $300 billion boondoggle to assuage George W. Bush’s oedipal conflict, planned from Day One in his White House, nine months before Bin Laden’s attacks. Your party cannot bail out and rebuild the cultural capital of the South one full year after Hurricane Katrina. Your party cannot pass a decent minimum wage bill nearly a full decade after the last one. Finally, your party is full of cant: hypocritically pious, pseudo-religious palaver, intended to camouflage your insanely insatiable greed and lust for absolute, tyrannical power. Gerald Dugan]

——————————————————————————–

Santa Fe Opera Presents The Tempest

Thomas Adès

New Production

American Premiere

July 29; August 2, 11, 17

The Cast

Ariel — Cyndia Sieden

Miranda — Patricia Risley

Ferdinand — Toby Spence

King Alonso — Chris Merritt

Caliban — William Ferguson

Prospero — Rod Gilfry

Sebastian –Keith Phares

Trinculo — David Hansen

Stefano — Wilbur Pauley

Gonzalo — Gwynne Howell

Conductor — Alan Gilbert

Director — Jonathan Kent

Scenic & Costume Designer — Paul Brown

Lighting Designer — Duane Schuler